Japan has lots of rules. Rules for how to sit, order dinner, dress, and speak.

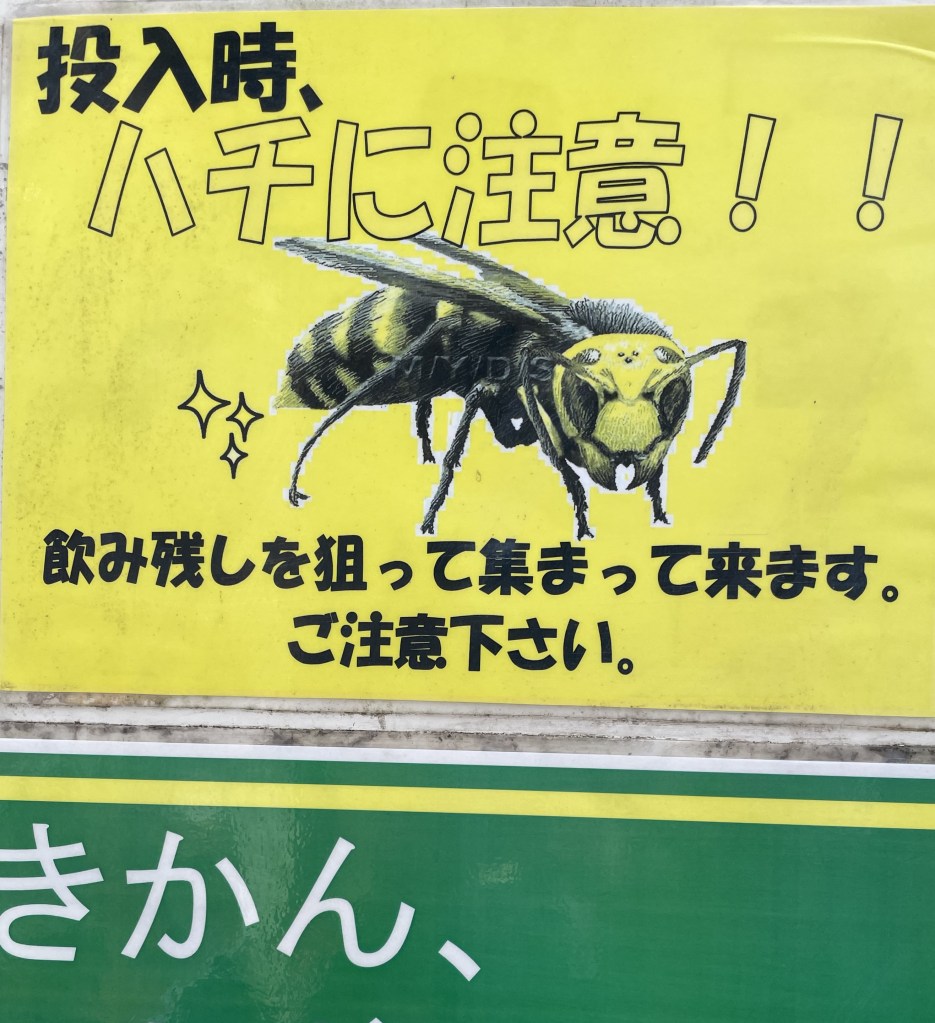

Most of these are unspoken, and many are written in little pamphlets or printed on signs. These kinds of rules are everywhere in the world but – usually with fewer pictures. The underground train stations have kiosks of fun guidebooks- filled with cute characters fainting in front of trains. I can’t read Japanese, but I imagine they say, “Caution!! Don’t faint in front of trains!” The many posters lining the walls probably say something similar. Apparently, dangers are everywhere, and the city of Tokyo wants to help you avoid them.

I, for one, am grateful for pamphlets pointing out the obvious. Because it helps me be courteous to people who live and work in Tokyo. On the train, there are benches that are reserved for the elderly and infirm. Now I know, and don’t sit there so the people who need them can use them.

Spoken word doesn’t usually come with pictures so it’s more difficult. I already said I can’t read Japanese, well, I can’t speak it either. And most people I ran into couldn’t speak English. Travel guides make it seem like everyone in the world speaks English but I didn’t meet many people (I met exactly one) who could answer novel questions, and had many bewildering conversations.

It seems like language fluency is a complicated thing. Although it’s a sliding scale people will likely self-report as one extreme or another (“I’m fluent” or “I’m not”). The woman I met who could ask questions and respond naturally, said she was really very bad at English– al la mode Japan. What you gunna do.

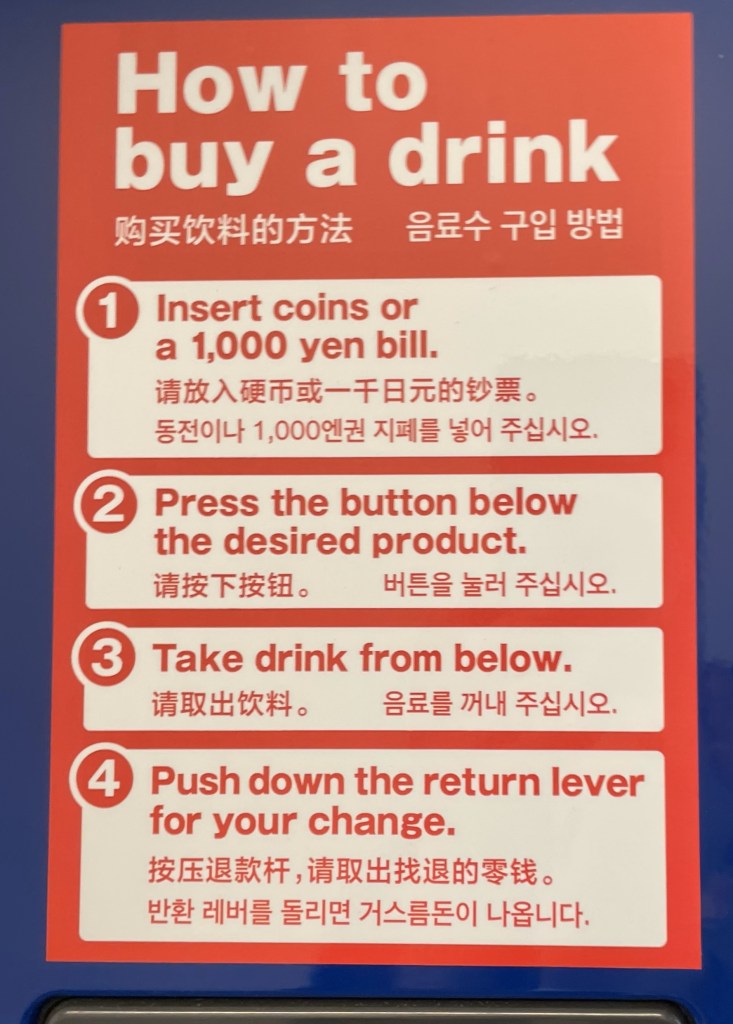

So, many things are lost on me in Tokyo. I am confused when I hear a woman in a grocery speaking in polite form, and still feel like she’s being a bit rude. I worry that she’s annoyed that I’m (like an idiot) using coins in the no-cash machine and she probably is annoyed. She’s got no time for my shenanigans; she’s got a job to do! Which goes to show you that grammatical politeness isn’t actual politeness.

But the flip of polite words having rude undertones is that sometimes what sounds rude is actually someone looking out for you.

A waitress told us (in English) that if we didn’t order a meal, we couldn’t go to the salad bar. But we would have understood that when she removed the salad plate. So why did she struggle to say it in English when she could have just implied it?

Because being explicit tells people who may not know (like foreigners) the social expectations. It helps people avoid the awkwardness of bungling things and the embarrassment of inconveniencing others. I would have been pretty mortified if I had eaten something I didn’t pay for. She saw the possible misinterpretation and took the time to explain the parameters of the meal for my sake more than hers. Because telling people the rules can be a kindness.

Leave a comment